- Home

- Various Authors

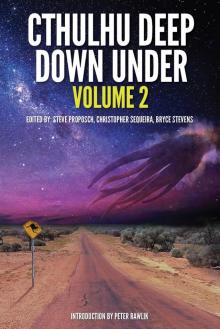

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2 Read online

IFWG AUSTRALIA Dark Phases Titles

Peripheral Visions (Robert Hood, 2015)

The Grief Hole (Kaaron Warren, 2016)

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Vol 1 (2017)

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Vol 2 (2018)

Cthulhu

Deep Down Under

Volume 2

Edited by

Steve Proposch

Christopher Sequeira

Bryce Stevens

Introduction by

Peter Rawlik

A Dark Phases Title

This is a work of fiction. The events and characters portrayed herein are imaginary and are not intended to refer to specific places, events or living persons. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are solely the opinions of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the publisher.

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2

All Rights Reserved

ISBN-13: 978-1-925759-46-4

Anthology Concept Copyright ©2017 Steve Proposch,

Christopher Sequeira & Bryce Stevens

V1.0

All stories in this anthology are copyright ©2018 the authors of each story, with the following variations: Introduction copyright ©2018 by Peter Rawlik. ‘The Pit’ by Bill Congreve, ‘The Island in the Swamp’ by J Scherpenhuizen, ‘Depth Lurker’ by Geoff Brown (originally writing as G.N. Braun), ‘Where the Madmen Meet’ by T S P Sweeney and ‘The Seamounts of Vaalua Tuva’ by David Kuraria first published in Cthulhu: Deep Down Under limited run publication (Horror Australis, 2015) edited by Steve Proposch, Christopher Sequeira & Bryce Stevens.

Frontispiece art by Andrew J McKiernan; back art by David Heinrich.

This ebook may not be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in whole or in part by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the express written consent of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

IFWG Publishing Australia

Melbourne

www.ifwgaustralia.com

This collection is dedicated to Don Boyd

Introduction

Peter Rawlik

Cthulhu.

When a book includes that word, what is that supposed to mean? For some, it is meant to clearly convey that the volume in question will be directly related to the Cthulhu Mythos and chock-full of references to Lovecraft Country, Miskatonic University and its faculty, and the pantheon of cosmic alien pseudo-deities including Yog-Sothoth, Yig and, yes, Cthulhu. For others, it is more vague, setting the tone for a collection of tales that invoke the Lovecraftian without being bound by its setting and trappings. It might be more appropriate to use the word “Lovecraftian” or “Weird”, or even “Cosmic”, but these words don’t have the same gravitas as “Cthulhu”, which is why Mike Davis entitled his anthology Autumn Cthulhu and S.T. Joshi’s anthology series Black Wings, has morphed into Black Wings of Cthulhu. This is not to say that Lovecraft can’t be used to sell in the mainstream, as Ellen Datlow has shown in her anthologies Lovecraft Unbound, Lovecraft’s Monsters, and Children of Lovecraft, but when it comes to weird literature nothing implies anti-anthropocentric cosmic horror more than the word “Cthulhu”.

And I should know, I’ve been reading Cthulhu since I could read, since before I could tell the difference between Lovecraft and Derleth, since before there was little else to read but Lovecraft and Derleth and a few volumes by Brian Lumley and Ramsey Campbell, two authors that, having started with the same source material—the same inspirations—went in wildly different directions. That right there is one of the joys of the Cthulhu Mythos: different authors can be inspired by and reinterpret and redirect things—the source material—in totally different ways.

The stories presented here in Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2 are a rare and heady mixture of talents, highlighting the diversity of direction that Lovecraftian fiction can be taken, and while some of these stories could be transplanted to other locales, some are uniquely Australian, relying on the landscape that Australia encompasses, or by the place that Australia occupies geographically—on the edge of the world, not far from the uninhabitable bleakness of Antarctica, and overlooking the Pacific deeps, some of the most remote places on the planet. Is it any surprise that writers in such places have unique perspectives, have adapted and adopted local myth cycles, have succumbed to the madness of the lonely, inhuman and inhumane Cthulhu? I hadn’t expected such wonders, but in retrospect I should have, I should not have been surprised by the luscious, dark jewels that were sent to me to read.

In Sleeping Dogs, Kristyn McDermott gives us a protagonist named Ghost who has a most unusual and useful talent—the ability to find lost things, but, as she soon finds out, some things are better left lost, and for Ghost the horror might just be beginning. What is most interesting here is that the motivations behind Ghost’s employers remain unknown, at least to her. This makes Ghost an unwitting pawn in the action and pits her mercenary drives against whatever concerns she might have for the wellbeing of the human race. This dichotomy creates a building tension—we like Ghost, we want her to survive, but do we really want her to succeed?

Where McDermott’s story is firmly rooted in the Cthulhu Mythos, Slither by Jason Nahrung draws dread inspiration from Lovecraftian horrors and only hints at the existence of something terrible. Nahrung forces us to walk the line between confronting a horror, and the existential dread that is generated by something that creeps, seeps, slithers, even into the dark recesses of your brain.

Silvia Brown’s Melbourne Calling echoes this same kind of concern. Haunted by what he thinks of as forbidden desires, a young man fights to keep his sanity only to be rescued by a kindred soul and a summer romance that drives the nightmares away. Only—as we older folk all know—romances are fraught with difficulties, which lead to doubts that can shake even the strongest of relationships. In the shadow of doubt the monsters come calling. To some, it might seem better to embrace the abyss and dive headlong into monstrous self-annihilation than to accept the angst-filled pedestrian world that haunts our teenage years.

Time and Tide by Robert Hood returns us to a more overt Cthulhu Mythos tale, one that should be applauded by the author’s rather bold attempt to invoke the weird in a most unusual manner. We are told that the sense of smell is the most evocative of senses, but it is rarely used, and rarely used as effectively as Hood has here, to convey not only the preternatural, but a fundamental wrongness to the universe, an inversion of the natural order of things that has dire consequences to the residents of Mollymook.

Lee Murray’s Dead End Town takes us back into the realm of personal horror, or perhaps personal apocalypse. Murray expertly avoids the tropes and trappings of Lovecraft, but at the same time mines the ichor and uncertain parentage that seems to accompany cosmic monstrosities and redirects them into a subtle but inescapable realm of body horror.

Where Murray’s tale is subtle, Bill Congreve’s The Pit is overtly Lovecraftian, and welcomingly so. A morality tale about the dangers of unregulated industry, Congreve manages to pay homage to Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth, At the Mountains of Madness and The Color Out of Space without precisely referencing any one of them. It’s refreshing to see a tale that roots itself firmly in the past, recognizes its origins, but isn’t slavishly obsequious. It’s reminiscent of a Delta Green tale or something that would have been at home in Ed Stasheff’s recent anthology Corporate Cthulhu, but it is firmly rooted in the vast desolate landscape that haunts Australian nightmares.

Subtleness goes out the window in Jan Scherpenhuizen’s The Island in the Swamp in which an aficionado of fringe theories sets out to debunk or prove

a latest new-age pseudoscientific theory. Either way he will improve his standing amongst his friends and family, unless of course things go horribly, terribly wrong, which of course they do. Here once again, the Lovecraftian oeuvre is evoked without actually delving into the trappings, though it might be thought of as Cthulhu through the lens of Clive Barker.

Where the Madmen Meet by T.S.P. Sweeney begins innocently enough as the tale of soldiers back from war trying to adjust, but as it progresses it veers directly into a sequel to one of Lovecraft’s most infamous of tales. I will admit that while the first person narrative initially put me off, particularly because of the ending, I’ve come to realise that the horror invoked here doesn’t end with death. Think about it, think about how this story is even possible, and then shudder, just a little. Then, think of the children.

The Seamounts of Vaalua Tuva by David Kuraria is perhaps the most ambitious of stories in this volume. There’s hints of a zombie outbreak going on in the background, but that seems unimportant to the main action of the tale, which involves the protection of civil society amongst the Solomon Islands from seafaring warlords, amidst tall tales of an indigent tribe blamed for all sorts of ills. As things progress, details that seemed unimportant suddenly come to the forefront, and suddenly it is no longer clear who is in charge and what is legend. Lovecraftian without being pastiche, I suspect someone, somewhere, will adapt this into a rather gruesome and punishing scenario for a Call of Cthulhu home game.

Geoff Brown’s The Depth Lurker is reminiscent of both The Statement of Randolph Carter and Pickman’s Model, invoking the fear that goes with descending into the unfathomable depths of the Earth to encounter the unknown. Present as well is the dread that is derived from the most common of acts or objects once one has survived such acts, but can’t quite shake the idea that horror is lurking just beyond the corner. In many ways The Depth Lurker is well paired with Bill Congreve’s The Pit, for both rely in part on the isolation of the Australian landscape, magnified by descent into the darkness below. But where Congreve’s hero rose to the challenge, Brown’s protagonist must find a way to live with what he has seen—if you can call his solution living.

As I have said, luscious, dark jewels that I hadn’t—but should have—expected, and all unique and vibrant interpretations of the weird, the cosmic, the Lovecraftian Cthulhu, even in his absence. They are, in a way, fitting successors to the weird traditions that spawned Joan Lindsay, Vol Molsworth, David Unaipon, and Ernest Favenc. I look forward to the day when my shelves run rampant with weird literature from what Dorothea Mackellar called “the Sunburnt Country”.

Peter Rawlik, 2018

Sleeping Dogs

Kirstyn McDermott

Ghost has the start of a headache, the start of what she hopes won’t morph into one of her colour-soaked migraines. Even if this job doesn’t pan out, she hardly has the time to lay up in bed for a day or two with a cool washcloth over her eyes. She rubs at her temples. Squeezes her earlobes. Someone once told her that worked. Sometimes it does.

It’s been at least a quarter hour, maybe more, since she was escorted into the room by the tall woman with the artfully expressionless face and asked—instructed, more like—to take a seat. Ghost doesn’t reach for her phone to check her messages. She doesn’t tap her foot on the polished wooden floorboards. She doesn’t pick at the skin around her fingernails. She’s been asked to wait, and wait she will. Patiently. Visibly. She suspects that might be part of the interview. She suspects there’s at least one spy-cam somewhere in the room, feeding its sneaky live report back to whoever wants to see just how much patience Ghost is able to summon.

“More than you know,” she whispers through unmoving lips.

The room is half-office, half-library, and the ultra-tidy desk before which Ghost sits would be long enough for her to use as a bed. It’s made from a dark, reddish brown wood, most likely mahogany—most likely real mahogany, maybe even antique mahogany—that matches what she can see of the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves lining the walls, as well as the rolling ladder in the corner, and the exposed wood on the pair of lion-footed Georgian armchairs over by the window. Their flawless, cream-coloured upholstery must of course be the result of more recent renovations; no way could such fabric survive the ravages of almost a century unscathed.

Still, the room oozes wealth. This job should pay well.

Ghost waits.

Ten more minutes pass before the door finally swings opens and a woman in a modest but finely tailored suit marches into the room. Her hair is steel grey, cut into a sharp, chin-length bob, and her fingernails sport well-manicured French tips. She looks exactly like the sort of person who belongs behind that neat mahogany desk and, indeed, behind the desk is precisely where she sits herself.

Keeping a few paces behind, the tall woman who escorted Ghost previously closes the door before taking up a position at the older woman’s side. “Ms Thurston,” she says, “this is Ghost.”

“Not your real name?” Ms Thurston’s eyes are a blue so pale they’re almost grey. She doesn’t blink.

Ghost shrugs. “Real enough for me.”

The older woman holds her gaze for a moment longer, then nods. By her right elbow, resting on a small stack of papers, is a polished green-black stone roughly the same size and shape as a boiled egg sliced in half. Ms Thurston picks up the stone and places it right in front of Ghost.

“Did you notice my paperweight?” she asks.

Ghost nods, not looking at the stone. Of course she noticed it, just as she noticed the empty in-tray where those papers had probably lain, sans weight, until five minutes before her appointment. Just as she noticed the Art Deco lamp with the inlaid mother-of-pearl shade, and the Montblanc fountain pen that likely cost more than a month’s rent in the crappy Marylebone studio where Ghost has been living for almost a year, as well as the complete lack of framed photos or uniquely personal items anywhere in sight. It’s her job to notice things. To see what others might overlook.

“Pick it up,” Ms Thurston says.

“I’d rather not.” Ghost doesn’t know why she refuses. It’s dumb, but she doesn’t feel like even looking at the stone too closely, let alone touching it.

“Please.”

Clenching her teeth, Ghost reaches out and takes the stone between finger and thumb, like it’s something dead, or worse. Nothing happens. It’s a little heavier than she expected, smooth and cool and polished so highly she can see her silhouette reflected in its surface, and now she really, really wants to put it down. The pressure in her head has intensified and she wishes she had a glass of cold water.

After a minute that feels like an age, Ms Thurston holds out her palm. Ghost drops the stone so quickly it almost bounces, but the older woman catches it gracefully. She opens a desk drawer and retrieves a small black bag—like velvet, but darker somehow, less lightful—then drops the stone inside.

“Our missing artefact is crafted from similar material,” she says. “I needed to know how you would react before we proceed.”

“Well, I won’t be asking for a free sample.”

She smiles, lips stretched thin. “In some people, it can arouse rather…covetous emotions. You, however, sat here for thirty minutes with scarcely a glance in its direction. A passing grade, Lavinia, don’t you think?”

Beside her, the tall woman nods. “I believe so, ma’am.” Her face has softened somewhat, relaxed, a corner of her mouth twitching upwards. Ghost reckons she would be the type to unravel delightfully after a few drinks down the corner pub, spilling crude jokes and cider until the early hours. Though she doesn’t suppose she’ll have a chance to find that out for herself.

“You’re not as old I expected,” Ms Thurston is saying.

Ghost swallows a sigh. She’s short and has always looked much younger than her age—she was being regularly carded well into her twenties; sometimes still gets asked—and turning thirty last month didn’t seem to magically gift her with the kind of face that si

gnalled, hey, I’m an actual grown woman, please take me the fuck seriously.

“Is that a problem?” she asks, her tone carefully neutral.

“Merely an observation.” Ms Thurston pulls a large envelope from the stack of papers and slides it across the desk. “This is what we need recovered. It’s an artist’s impression, drawn from the memories of two people who’ve seen the object firsthand, albeit some time ago now. ”

The drawing gives Ghost the creeps. Sketched from three-quarter view, it looks like some kind of weird gargoyle, winged and crouching on a low pedestal, with an octopus in place of its head—if an octopus could have as many as a dozen or more tentacles writhing around its face. The creature’s two hands—paws?—are resting on its knees, with huge claws curving downwards, and its body seems to be covered in scales. The pedestal itself is covered in squiggles that might be meant to represent inscriptions of some kind, but there’s a question mark next to it. Ghost taps the page. “What’s this about?”

“One of the gentlemen described a plinth with sigils. The other swore the figure was carved without a platform of any kind, but with markings underneath.” Ms Thurston sighs. “They are quite elderly, you understand, in their nineties. Their recollections may be somewhat fallible.”

“How long ago did they see this thing?”

“Approximately sixty years.”

Ghost raises her eyebrows. “There’s no one else?”

“Anyone else who claims to have laid eyes on the artefact is dead. It has been missing for quite some time.” Ms Thurston leans forward, her hands clasped tight together. “Will you be able to find it, or not?”

In the corner of the page, the artist has scribbled 5”/12cm. At least the thing is small. “Can I keep this?” Ghost asks.

Ms Thurston glances at Lavinia, who nods. “We’ve made several high res copies, ma’am. Print and digital.”

“The original would be best,” Ghost says.

The older woman regards her silently for several seconds. “We will need it back, once you’re done.”

Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen

Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen Gods & Mortals

Gods & Mortals St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013

St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013 firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology

firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology Warcry: The Anthology

Warcry: The Anthology Sacrosanct & Other Stories

Sacrosanct & Other Stories Ultimate Heroes Collection

Ultimate Heroes Collection Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2 Erotic Classics II

Erotic Classics II Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6

Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6 Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12

Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12 International Speculative Fiction #4

International Speculative Fiction #4 Fyreslayers

Fyreslayers One Night In Collection

One Night In Collection Mortal Crimes 2

Mortal Crimes 2 Some of the Best from Tor.com

Some of the Best from Tor.com Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Malfeasance Occasional

The Malfeasance Occasional Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1 School's in Session

School's in Session International Speculative Fiction #5

International Speculative Fiction #5 Erotic Classics I

Erotic Classics I Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell

Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell Mortal Crimes 1

Mortal Crimes 1 The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels

The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels Don't Read in the Closet volume one

Don't Read in the Closet volume one Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original The Fitzwarren Inheritance

The Fitzwarren Inheritance All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse

All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12

Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12 Kiss Kiss

Kiss Kiss Dog Stories

Dog Stories Bad Blood Collection

Bad Blood Collection