Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen

Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen Gods & Mortals

Gods & Mortals St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013

St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013 firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology

firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology Warcry: The Anthology

Warcry: The Anthology Sacrosanct & Other Stories

Sacrosanct & Other Stories Ultimate Heroes Collection

Ultimate Heroes Collection Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2 Erotic Classics II

Erotic Classics II Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6

Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6 Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12

Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12 International Speculative Fiction #4

International Speculative Fiction #4 Fyreslayers

Fyreslayers One Night In Collection

One Night In Collection Mortal Crimes 2

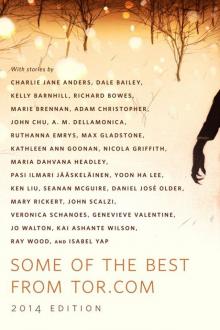

Mortal Crimes 2 Some of the Best from Tor.com

Some of the Best from Tor.com Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Malfeasance Occasional

The Malfeasance Occasional Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1 School's in Session

School's in Session International Speculative Fiction #5

International Speculative Fiction #5 Erotic Classics I

Erotic Classics I Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell

Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell Mortal Crimes 1

Mortal Crimes 1 The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels

The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels Don't Read in the Closet volume one

Don't Read in the Closet volume one Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original The Fitzwarren Inheritance

The Fitzwarren Inheritance All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse

All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12

Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12 Kiss Kiss

Kiss Kiss Dog Stories

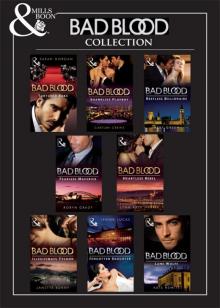

Dog Stories Bad Blood Collection

Bad Blood Collection