- Home

- Various Authors

The Conan Compendium Page 8

The Conan Compendium Read online

Page 8

"And now all Cimmeria will suffer because they didn't," said Loarn.

"Take the news north," said Mordec, shrugging again. "If all the clans in the countryside joined against the invaders ― He broke off and laughed. "If that happened, it would be a miracle, and when was the last time Crom worked a miracle in these parts? He's not that sort of god. He wants his folk to work the miracles."

Loarn grunted. He did not quarrel with Mordec; no Cimmerian could have, not where their god was concerned. The blacksmith had spoken only the truth about the dour deity who watched over this tree-draped land and expected the people dwelling in it to solve their own problems without bothering him.

Conan came in just then, carrying a wooden tray with two mugs of ale, and with oatcakes and a slab of roasted pork ribs for the guest in the house. "Thank you, lad," said Loarn, and then, in surprise, "Mistress Verina! I know you're not well.

You did not need to trouble yourself for me."

From behind Conan, his mother said, "It is no trouble, Loarn." A moment later, she gave herself the lie, coughing till her face went a dusky purple and blood-flecked foam clung to her lower lip.

"Get into bed, Verina," growled Mordec. He snatched one of the mugs of ale from the tray in Conan's hands and drained it at a single long pull. "Loarn is right―you do yourself no good by being up and about when you shouldn't."

"I do the honor of the household good," said Verina with quiet pride.

The blacksmith ground his teeth in a curious mix of frustration and fury. Verina was willing ―was perhaps even eager―to give up, to throw away, her own life to prove a point. Mordec had seen that years before, when her illness first came upon her. He often thought she used it as a weapon, turning her weakness against him where strength would not have sufficed. That he kept to himself. Had he spoken of it, it would only have ignited more strife between them. But he spent as much time away from the smithy as he could.

His absences, of course, only tightened the bond between Verina and Conan.

When she began to cough again, the boy anxiously asked, "Are you all right, Mother?" and started to go to her.

She waved him away, saying, "Tend to the guest in the house, if you please. I will do well enough."

Conan grimaced but obeyed. He heeded her better than he had ever obeyed Mordec, against whose iron will his own, equally hard, clashed at every opportunity. The smith grimaced, too, but for different reasons. He did not care for Verina's use of their son to show off her illness, but she had been doing it for years, and he had never found a way to stop her. He wished the mug he had drained had held twice as much ale.

Loarn, tactfully, said only, "Tell me more of the coming of the cursed Aquilonians. When I do go into the north country again, I will need to answer many questions, and I will want to have the answers right."

Before Mordec could reply, Conan did: "Not only soldiers have come to Cimmeria, but also farmers, and their women and children with them. The men from the south aim to take this land away from us forever."

"He speaks the truth," said Mordec. He scowled at Verina, then got off the stool on which he had been sitting. "If you will not go back to bed, at least come over here and sit down. Conan, bring your mother a mug of ale. Maybe it will lend her some strength."

The prospect of helping his mother was enough to make Conan listen to his father. He dashed back to the kitchen to pour the ale. Verina reluctantly perched on the stool Mordec had vacated. Had she and her husband and son been alone in the house, the blacksmith doubted she would have. Instead, she would have stubbornly stayed on her feet until she fell in a faint, which might not have taken long. But with Loarn watching what went on, she did not care to quarrel too openly with her husband.

"Here you are, Mother." Conan hurried up with another mug of ale.

"Thank you, Conan." Verina was polite with him, where she had wasted no courteous words on Mordec.

Loarn tore into his food, as a man will when for a long time he has not eaten so much as he would have liked. After only bones and crumbs were left, he licked his fingers clean and wiped them dry on the checked wool of his breeks. That done, he bobbed his head to Mordec. "I thank you kindly," he said. "You've always made a prime host, that you have, but you've outdone yourself now, times being so hard for you. To the ravens with me if I know how I can pay you back."

"Your company is enough," said Verina, determined to make everything seem as smooth as it could.

But Mordec shook his head. "If you want to repay me, Loarn, spread the word of what's happened here in the south far and wide, so the rest of Cimmeria does learn of it."

"I'd do that anyhow, for my own honor's sake," said the tinker. "I'll gladly do it for yours as well."

At Mordec's direction, Conan brought Loarn blankets and a pillow, so the guest

could stretch out on the floor by the forge, whose banked fire and hot brickwork would help keep him warm through the night. Giving Loarn a pillow meant Conan himself would go without one, but he did not grudge the peddler the best the house had to offer. Hospitality toward friends was as important a duty as vengeance against enemies.

Thirst for that vengeance made Conan's blood boil as he waited for sleep in his narrow bed. He imagined Count Stercus abusing Tarla rather than the girl from Rosinish. He imagined himself slaughtering Stercus and all the Gundermen and Bossonians who followed him. Such gore-soaked images helped soothe the boy, as softer toys might have soothed children in softer lands.

For his part, Mordec was also a long time finding slumber.

What would the Cimmerians still free do when they learned some of their cousins had passed into Aquilonian dominion? The blacksmith hoped such news would inflame them to come to their countrymen's rescue. That was what he hoped, but how much truth mingled with hope? The rest of the Cimmerians might easily decide the men of the south had proved themselves weaklings who deserved whatever happened to them. Like its god, this country's people had scant forgiveness in them, scant tolerance for weakness.

But they did have the barbarian's innate love of freedom. Mordec pinned his hopes there. Surely the other Cimmerians would see that, if one part of their land fell under King Numedides' iron first, the rest could easily follow. Surely they would want to make sure such a disaster did not befall them. Surely they would ―would they not?

Grunting worriedly as sleep overtook him, Mordec at last began to snore.

Chapter Five

Wolves and Demon

Winter came early to Cimmeria, as it did more winters than not. Winds howled down from the north, from the ever-frozen lands of Vanaheim and Asgard. When

times got hard, red-haired and blond wolves who ran on two legs might swoop down on Cimmeria to carry off what they could. In a usual year, men from southern Cimmeria could fare north to help drive back the marauders, who even to them seemed savage. Now, though, with Count Stercus and the colonists carving out a toehold for King Numedides of Aquilonia here in the south, the clans near the northern borders would have to shift for themselves if danger came their way.

No word of rampaging AEsir or Vanir came down to Duthil: only one blizzard after another, blizzards that piled the snow in thick drifts and left trees so covered in white, their greenery all but disappeared. Hunting was hard. Even moving was often hard. Winter was the bleak time of the year, the time when folk lived on what they had brought in during the harvest and hoped they would not have to eat next year's seed grain to keep from starving.

For those who did not make their living directly from the fields, those like Conan and his family, winter was an even chancier season than for most others. If people had not the rye and oats to give Mordec for his labor, what were he and Conan and Verina to do? They had had hungry winters before. This looked like another one.

Despite the drifted snow, Conan went hunting whenever he could. Against the cold, he wore sheepskin trousers and a jacket made from the hides of wolves Mordec had slain. A wolfskin cap with earflaps warded his head against win

ter.

Felt boots worn too large and stuffed with wool kept his feet warm.

Even with all that cold-weather gear, he still shivered as he left the smithy. The icy weather outside seemed to bite all the harder after the heat that poured from Mordec's forge. Now, instead of the fire in that forge. Conan's breath smoked.

"Out hunting, Conan?" That was Tarla, the daughter of Balarg the weaver, scooping clean, fresh snow into buckets to bring it indoors to melt for drinking and cooking water.

He nodded. "Aye," he said, and even the one word seemed a great speech to him.

The girl's smile was like a moment of sunshine from some warmer country.

"Good fortune go with you, then," she said.

Awkwardly, Conan dipped his head. "Thanks," he said, and hurried away toward the woods.

Not far from Duthil stood the encampment full of Bossonians and Gundermen.

By now, it seemed as much a fixture on the landscape as the village itself.

Sentries stood guard beyond the palisade around the cabins that had replaced the soldiers' tents. One of them waved to Conan as he went off toward the forest. He pretended not to see. Waving back would have been confessing friendship for the invaders.

He had not been in the woods for long before he heard Aquilonian voices cursing.

He slipped silently through the trees toward the sound. A supply wagon on the way up from Fort Venarium to the smaller camp outside of Duthil had bogged down in deep snow.

"Don't do that!" said a guard as the driver raised his whip to try to lash the horses forward. "Can't you see we need to clear a path for them?"

"Mitra! Let them work. Why should I?" said the driver. "This weather's not fit for beasts and barbarians, let alone for honest men to be out and about in."

Conan did not follow all of that―his grasp of the invaders' tongue was far from what it might have been, though nonetheless surprising for one with but a few months of informal and sketchily acquired knowledge behind him. The gist, though, seemed plain enough. Snarling deep in his throat, he reached over his shoulder for an arrow. He could not have said whether he wished to shoot the driver more on account of his scorn for Cimmerians or his callousness toward the team.

In the end, he did not loose the shaft that would have drunk the soldier's life.

Driver and guard never knew their lives stood for a long moment on the razor's edge. They never knew one of the barbarians they despised had stood close enough to kill them, but had mastered his murderous rage and moved on. Silent as snowfall, Conan glided deeper into the forest. He had come forth to hunt game, not men.

Snow buntings chirped in the trees. They were some of the few birds that did not flee to warmer climes when winter came. Conan was fond of them because of that. Even as woodswise as he was, he had a hard time spying them. They were white and buff, almost invisible in the snow. Only when they flew did their black wingtips give them away. Those wingtips reminded him of an ermine's nose and tail tip, which stayed dark even after the rest of the creature went white to match the winter background.

If he got hungry enough, he supposed a stew of snow buntings would keep him from starving. But he would have wanted to frighten them into nets, not try to shoot them on the wing. They were swift and agile flyers, and no one bird had much in the way of meat. The arrows he lost were unlikely to repay the catch he made.

He did keep his eyes open not for ermine but for other creatures that went white when winter came: plump hares and the ptarmigan that feasted on pine and spruce needles through the cold weather. The hares' black eyes and noses and the black outer tail feathers of the ptarmigan sometimes betrayed them to the alert hunter.

Because of what they ate at this season, ptarmigan were less tasty in winter than in summer, but they were meat, tasty or not, and a hungry man could not be choosy.

No one and nothing hungry could be choosy in wintertime. Only little by little did Conan realize he had gone from hunter to hunted. He had heard wolves howl several times that day, but not so near as to be alarming. Hearing those howls in the distance lulled him for longer than it should have when he heard them closer.

Thus it was with a start of horror that he realized a pack had found his trail.

His first impulse, like that of any hunted wild creature, was to run like the wind in a desperate search for escape. He mastered it, as he had mastered the urge to murder. Both would have given momentary satisfaction, and both would have brought disaster in their wake. Wolves could outrun men. Any man who reckoned otherwise but doomed himself.

Instead of running wild and exhausting himself, Conan moved with grim purpose, seeking a spot where he might make a stand against the beasts to which he was

but so much meat. And, before long, he found one. Had he fled blindly, he might well have dashed past without realizing it was there.

Two boulders, each of them taller than a man, came together to leave a space between them shaped like a sword point, protecting him from either side. At the very tip, where there would have been an opening, stood the trunk of a tall spruce, against which he set his back. He had his bow, his arrows, and on his belt a long knife his father had forged. The wolves had their teeth and claws. They also had the innate ferocity of the wild. They had it, and so did he.

Their voices rose to high, excited howls when they realized they had brought him to bay. The first wolf loped toward him, snow flying up from under its feet, red tongue lolling out of its red mouth, slaver dripping from yellowish fangs, amber eyes gleaming with hate and hunger.

The pack leader leaped. Conan let fly. He shot it full in the chest with the one envenomed arrow he carried. He had to be sure, certain sure, of this kill. So potent was the poison that the wolf had time for but the bare beginning of a startled yip before it slammed down dead on the snow. Its blood steamed scarlet beneath it.

Conan's next shaft, driven by all the power in his smithy-trained arms, was in the air less than half a heartbeat later. It sank almost to the fletching in the eye of the wolf closest behind the leader. That beast, too, died in the instant of its wounding.

The third arrow, also quickly shot, sank deep into the flank of the next nearest wolf. That was not a mortal shot, but the wolf belled in pain and ran from the man-thing who had inflicted such torment on it.

Three more shafts saw another wolf dead, one wounded, and one arrow flying far but futilely. Some of the yet unhurt wolves began tearing at the carcasses of a fallen comrade. In this desperate time of year, meat was meat, come whence it might. Gore stained the snow. Conan shot another wolf, and yet another, even as they fed.

But more of them kept him in their bestial minds. One sprang over the corpse of the first wolf he had shot while he reached for a fresh arrow. A civilized man would have gone on with the motion, knowing he would complete it too late, or

else would have hesitated before throwing down the bow and snatching knife from scabbard ―and, hesitating, would have been undone.

No hesitation lived in Conan. With the quicksilver instincts of the barbarian, he abandoned bow for knife, stabbing deep into the wolfs side even as it overbore him. Its rank breath stank in his nostrils as it snapped, trying to tear out his throat.

He held its horrible head away from him as he drove the knife home again and again, until his right arm was red with blood to the elbow.

All at once, the wolf decided it wanted no part of him, and tried to break away rather than to slay. Too late, for its legs no longer cared to bear its weight. It sank down lifeless on top of Conan.

The blacksmith's son flung its weight aside and sprang to his feet ere others could assail him. He seized his bow again and nocked an arrow, ready ― as he had been ready in the fight with Mordec ―to go on even to the death. He might die, but if he did he would die striving.

But the wolves had had enough. Those that still lived and were yet unwounded trotted off in search of easier prey. Conan's shout of triumph filled the silent forest with fierce joy. He killed two wolves that

were still writhing in the snow, then went about the grisly business of skinning the brutes ― all but the one its packmates had partially devoured. That done, he also cut slabs of meat from the carcasses. At this season of the year, in this harsh country, he would have eaten worse meat than wolf, and would have been glad to have it.

Burdened as he was, he found going back to Duthil harder than coming out from the village had been. He floundered deeper into snowdrifts, and broke through crust upon which he had been able to walk. Despite the cold, he was sweating under his furs and wool by the time he finally reached his home. The heat of his father's forge, which had been so welcome in wintertime, struck him like a blow.

Mordec was striking blows of his own, on an andiron he held against the anvil with a pair of black iron tongs. The smith looked up from his labor when Conan came through the door. "Are you hale, boy?" he demanded, startled anxiety suddenly filling his voice.

Conan looked down at himself. He had not realized he was so thoroughly drenched in gore. "It's not my blood, Father," he said proudly, and set the wolf names and the butchered meat on the ground in front of him.

Mordec eyed the hides for some little while before he spoke. When at last he did, he asked, "You slew all of these yourself?"

"No one else, by Crom!" answered Conan, and he told the story with nearly as much savage vigor as he had expended in the fight against the pack.

After Conan stopped, his father was again some time silent. This time, Mordec spoke more to himself than to Conan: "I may have been wrong." Conan's eyes opened very wide, for he did not think he had ever heard his father say such a thing before. Mordec turned to him and continued, "When next we go to war, son, I shall not try to hold you back. By the look of things, you are a host in yourself."

Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen

Lady Ambleforth's Afternoon Adventure by Ann Lethbridge, Barbara Monajem, Annie Burrows, Elaine Golden, Julia Justiss and Louise Allen Gods & Mortals

Gods & Mortals St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013

St. Somewhere Journal, July 2013 firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology

firstwriter.com First Short Story Anthology Warcry: The Anthology

Warcry: The Anthology Sacrosanct & Other Stories

Sacrosanct & Other Stories Ultimate Heroes Collection

Ultimate Heroes Collection Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2

Cthulhu Deep Down Under Volume 2 Erotic Classics II

Erotic Classics II Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6

Dynasties: The Elliotts, Books 1-6 Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12

Dynasties:The Elliots, Books 7-12 International Speculative Fiction #4

International Speculative Fiction #4 Fyreslayers

Fyreslayers One Night In Collection

One Night In Collection Mortal Crimes 2

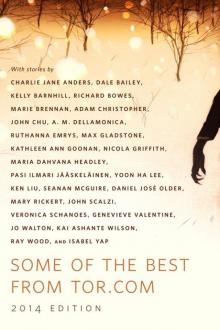

Mortal Crimes 2 Some of the Best from Tor.com

Some of the Best from Tor.com Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Howl & Growl: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set The Conan Compendium

The Conan Compendium The Malfeasance Occasional

The Malfeasance Occasional Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 4 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 2 Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1

Brides of Penhally Bay - Vol 1 School's in Session

School's in Session International Speculative Fiction #5

International Speculative Fiction #5 Erotic Classics I

Erotic Classics I Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell

Legends: Stories in Honor of David Gemmell Mortal Crimes 1

Mortal Crimes 1 The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels

The Classic Children's Literature Collection: 39 Classic Novels Don't Read in the Closet volume one

Don't Read in the Closet volume one Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2014: A Tor.Com Original The Fitzwarren Inheritance

The Fitzwarren Inheritance All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse

All Things Zombie: Chronology of the Apocalypse Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12

Hammer and Bolter - Issue 12 Kiss Kiss

Kiss Kiss Dog Stories

Dog Stories Bad Blood Collection

Bad Blood Collection